Executive Director Dr Gillian Dow’s welcome to Friends for the launch of our exhibition.

Emma at 200: from English Village to Global Appeal

Trustees, Patrons, Honoured Friends and members of our BlueStocking Circle, welcome to Chawton House Library for the launch of our exhibition ‘Emma at 200: from English Village to Global Appeal’. I’d like to start with by quoting Jane Austen’s creation Miss Bates: ‘It is such a happiness when good people get together–and they always do’

In March 1816, exactly 200 years ago, a new novel appeared with a lengthy preface. It began:

‘This is not, strictly speaking, a novel. It’s a tableau of the manners of the time. One will recognise the customs and habits of the small towns of the provinces… There are no enchanted castles, no giants, everything is natural’

Or rather, it began:

‘La Nouvelle Emma n’est point, proprement parler, un roman; c’est un tableau des mœurs du temps…’

Because the novel in question here was Jane Austen’s Emma in French translation – a novel that hit the shelves of Paris bookseller Arthus Bertand 200 years ago this very month. This is a remarkable turnaround, even for a period during which novels criss-crossed the Channel at speed.

It is well known that Emma was composed during a particularly turbulent period. Begun in January 1814, just before Napoleon’s abdication and exile, completed just after his escape and resumption of power, it was published only six months after the battle of Waterloo finally ended the war with France. The concerns of the novel, of course, are much closer to home. It has been seen as the most English of Austen’s novels. And yet that very same year – 1816 – the first American edition was issued in Philadelphia.

I don’t think anyone would challenge the idea that Emma is world literature now, in 2016. But this exhibition argues it was world literature from the outset, and suggests that we gain a great deal from looking at Emma in its global context from the moment it was published. For Austen’s fourth novel entered a literary marketplace that was steeped in European literature, and Austen herself responded to the literature of the age in her work. Emma can in many ways be seen to be a novel about reading and misreadings.

We start here, in the Great Hall, with the first French translation set alongside the first and second American editions – a homage to the journey Emma made that year, entirely unknown to her authoress. We acknowledge the pioneering role played by twentieth century bibliographer David Gilson in locating these early editions with one of his letters.

In the dining room, we think about the travels of Austen’s brothers, and whether Edward Knight – owner of this house – may have inspired the character of Mr Knightley, or indeed Frank Churchill. In the tapestry gallery, some of the books on display belonged to Austen’s nephews and nieces: all are mentioned in the course of the novel.

The largest section in our exhibition – in our brand new exhibition room – focuses on the publisher John Murray, the second of the House of Murray, long based at 50 Albemarle Street. Jane Austen moved to John Murray for the publication of Emma. In doing so, she linked herself to great Romantic figures such as Byron and Walter Scott, but also a great many of now much less well-known women writers – from the French Mesdames de Genlis and Staël, to Helen Maria Williams, the poet and polemicist based in Paris, to Maria Graham, who published travel writings from India, Chile and Brazil, to Felicia Hemans, who, when Emma was being read, was composing a poem inspired by the Elgin marbles. John Murray published them all – and indeed made a large part of his fortune through the publication of Maria Rundell’s Domestic Cookery. This exhibition places John Murray’s publication of Emma in an ambitious, and global, list of women writers publishing in all genres.

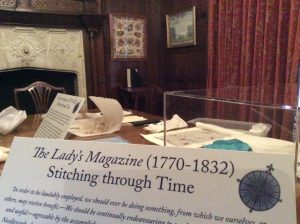

Next, we move to the Oak Room – the lady’s withdrawing room in Jane Austen’s time in the village, to think about female accomplishment, with sheet music, commonplace books, and an ‘enigma’ on display as a tribute to Emma Woodhouse, Harriet Smith and Jane Fairfax’s activities in the novel. Here, you can see an extraordinary display of contemporary embroidery – women’s work – inspired by patterns in The Lady’s Magazine, a publication which ran from 1770-1830, and which it is almost certain Jane Austen knew. Dr Jennie Batchelor is responsible for the Great Lady’s Magazine Stitch Off, and she will be in the Oak room to talk more about the project, and some of the exhibits.

On the long gallery, you will find a display of contemporary retellings of Emma – sequels, prequels and reimaginings of all kinds – and look out for some of the characters from the novel too!

In the cabinet in the lower staircase hall, a tribute to Shakespeare and women writers in the eighteenth century. This is inspired by Emma Woodhouse’s reference to A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the novel, and of course the four hundred year anniversary of Shakespeare’s death.

Finally, in the lower reading room, some thoughts on the contemporary and subsequent reception of Emma, with Walter Scott’s famous review of the novel published in the Quarterly Review, and Charlotte Bronte’s wonderful 1850 letter to her publisher W.S. Williams, on her reading of Emma, and her opinions of Jane Austen’s fiction more generally.

There are a great many treasures on display here. Some are of course treasures from our own collection. But many are treasures that have travelled from far afield. We are grateful to the University of Göttingen library in Germany, King’s College in Cambridge, Goucher College in Baltimore, the Murray archives at the National library of Scotland, the University of Aberystwyth special collections in Wales, the Huntington library in California, and private owners Simon Downing, and Professor Richard Jenkyns. Telling the global story of Emma has required cooperation on a global scale. And I’m grateful for the tireless work of my colleagues here to make sure it all happened, especially our Librarian Dr Darren Bevin, who I think – when I mentioned I thought we should do something on Emma – was imagining something a little smaller.

I am grateful, too, for the support of all those who donated towards the costs of hosting the exhibition. We couldn’t have thought about it at all without the support of our Texan friend Sandra Clark, who donated her first edition of Emma to us several years ago, and who is a generous supporter of all our activities. Without a large grant from the Garfield Weston foundation, we wouldn’t have the display cases we needed to house the items in proper conditions. My own institution, the University of Southampton, contributed generously to the production of the interpretation. And several Austen societies, and a great many individuals, gave generously too. Thank you to all of them.

And thank you to all of you, for coming to help us ‘launch’ the exhibition. My suggestion that we break a bottle of champagne over the display case was met by Darren with mutterings about it being ‘curatorially unsound’. So I’m going to ask Joanna Trollope, our newest patron, and champion of the Chawton House Library Friends, to lift off the cover, and declare this exhibition open.

And thank you to all of you, for coming to help us ‘launch’ the exhibition. My suggestion that we break a bottle of champagne over the display case was met by Darren with mutterings about it being ‘curatorially unsound’. So I’m going to ask Joanna Trollope, our newest patron, and champion of the Chawton House Library Friends, to lift off the cover, and declare this exhibition open.